“Money doesn’t make you happy. I now have $50 million but I was just as happy when I had $48 million.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Arnold Schwarzenegger was perhaps the leading actor of my childhood. A close second being Roger Moore in his seven Bond outings, or Harrison Ford in Witness, The Fugitive, and as Indy. Finally, Bruce Willis as John McClane and his subsequent clones. But for me, in terms of a solid, name above the title, film-for-film action star, it was all about Arnie.

In the mid to late-eighties, the regularity in which films were shown (and repeated) on UK terrestrial telly pretty much dictated my taste. Back then, if it was screened, and I was somehow made aware before hand via trailers, I’d record it, label it, rip off the black tab if it was half-decent, and hang onto it. Hordes of VHS tapes would crowd our living room cabinets, and my modest bedroom, which would eventually overflow to fill the entire sliding door storage space beneath my bed.

Despite my protestations, my parents resisted the might of BSkyB, preventing me from gorging myself on more potential filmic treats. The folks didn’t cave in to Sky Digital until around 1999, which was still a “better late than never” blessing, with Sky Movies, Sky Box Office, Film4, TCM, etc. broadening my cinematic horizons in terms of contemporary and classic film protein – if a little delayed to drastically influence my early years film education.

Until then, Arnie on ITV had to do. I endeavoured to carve out watchable pan and scan, cut to shreds, dubbed over with less offensive language (and strong bloody violence omitted altogether), tracking-warbled bastardisations of Predator, Total Recall, Twins, The Running Man, and Commando. Predator’s tracker, Billy, being chillingly relieved of his spinal column, and Dillon’s gruesome one-arm-severed submachine gun rebellion against the creature, were left on ITV’s cutting room floor. T2’s bar room shanking, and hot stove biker guy shuffle were also frustratingly censored.

So, why was Arnold my numero uno? Why did I, other than First Blood, disregard Sylvester Stallone and his entire Rocky saga? Why, in spite of rave reviews from school mates, did I ignore “The Muscles from Brussels,” Jean-Claude Van Damme? Largely reject Chuck Norris, aside from a few repeat viewings of The Delta Force’s Major McCoy’s standing motorcycle crescendo? Spurn Dolph Lundgren, again, aside from a single-watch of Universal Soldier as a VHS rental? Most bizarrely, why did I ever accept the sloth-like Steven Seagal? Was it all arbitrary? Did the limited video shelves and TV showings dictate my taste entirely? Was it as simple as just devouring whatever was plonked in front of me? Perhaps.

I never much went in for the inspirational aspects of Stallone’s Rocky movies. In fact, I didn’t see any until I was in my early thirties. Even as a boy, they seemed preachy. They always felt forced. But I couldn’t resist Arnold’s efforts – whether he was a cybernetic organism sent back in time to kill (or protect) one of the Connors, outwitting a mandibled alien hunter in the jungles of Central America, escaping an ultra-violent futuristic game show, meeting triple-boobed hookers on Mars, hanging out with his garbage-twin Danny DeVito, obliterating an entire army to rescue his kidnapped daughter, Jenny, or good-sportingly singing “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” to a bunch of unruly rugrats – his choices always appealed.

Ok, maybe not always. There were caveats. The two, made-to-measure, sword and sandals Conan movies, and Red Sonja, were one-watch deals, as spells and sorcery wasn’t exactly up my street, and the similarly-titled Raw Deal and Red Heat somehow got muddled and merged as one forgettable film.

A blokey gym-off is perhaps the furthest thing from my idea of a grand day out. As a kid, however, I was intrigued by the WWF wrestling, soap opera nature of it all. These real-life, jacked-up superhumans were my entertainment, my soap opera, my action stars. I’d gladly sit and watch Suburban Commando purely because Hulk Hogan and The Undertaker were in it. I’d wear out my Wrestlemania VIII tape, rewinding and rewatching The Ultimate Warrior’s chill-inducing sprint to the ring to heroically rescue the Hulkster from “Sycho” Sid Justice and Papa Shango’s assault. Just like these superstars of the squared circle, Arnie, was omnipresent.

This, at least now, seems contradictory to my personality. What I enjoy today is observing these muscle bound macho men from a comfy armchair as a kind of fascinating freak show. The competitive-natured, bantering boys’ club mentality of Arnold’s inner circles – explicitly showcased in Pumping Iron, Predator, and its revealing behind the scenes DVD making of, If It Bleeds We Can Kill It, is something I was largely born without.

I have, at various times in my life, been a contender for skinniest fella in the world, and would have been snapped like a twig by a brute the size of Arnold. I don’t care about physical fitness beyond having a relatively healthy body, but anything beyond that is vanity and I tune out. There’s no gym in sight. No sculpting of my physique going on. Anyone aspiring to six-packs and Instagram summer-ready bods are lost souls in my book. So the motivational speeches, and superiority complexes of the bicep-endowed alpha males, I find harmless and amusing. All power to you if your goal in life is to look like He-Man, but I personally think it’s masturbatory, and a waste of time, energy, and money.

But on the silver screen, that hulking mass of a human is paradoxically impressive to me. Again, Arnie is bigger than reality, like an artist’s rendering – a souped-up, sculpted hero, ripped (literally in the case of Conan) from the pages of a comic strip. In fact, during the production of, or prior to making Predator, a Sgt. Rock movie was discussed as a potential Arnold vehicle, and is even teasingly referenced in Hawkins’ comic book of choice during the closing credits (which I nicked for the outtakes reel for my graduation film, The Wilds, back in 2007 – keep your eyes peeled at the 2:31 mark for a few youngling Rewinders).

Yes, he’s a gigantic ham at times, but who else could have played Conan the Barbarian? Arnold was too big for Hollywood. Filmmakers and studios had to mold movies to fit this beast with an inhuman physique, massive-mouthful’d unpronounceable name, and an accent thick enough that, at one point, no one could understand a word he said (see the eventually dubbed, Hercules in New York aka Hercules Goes Bananas).

I’m reminded that (friend of the show) Lance Henriksen was originally set to portray The Terminator, but the sheer spectacle of Arnold won out for James Cameron, apparently against all odds, as his entire T-800 concept was that this machine-in-disguise needed to blend in seamlessly with the common man on the street. Where on Earth would Arnold Schwarzenegger ever blend in? Arnold was practically otherworldly. This illusory flaw in his appearance was soon spun into gold when filmmakers began to follow suit and tailor big-budget futuristic sci-fi blockbusters to fit his broad frame and peculiar cadence.

Why is this killer robot Austrian? As a kid, I was either too petrified or dumbfounded to notice this curious conundrum. Yet, conversely, in Commando, when John Matrix plummets from the landing gear of a plane, only to pop-up as if he were merely bouncing on a crash mat, and go about his mission – I noticed the implausibility, but it never severed my suspension of disbelief, my loyalty to the film, or its brawny star.

None of these shortcomings really matter in Predator. His character is named “Dutch” to hide his ambiguous Euro-weirdness behind a vague veil, and explain away an accent your average American Joe could never place anyway. He’s buff, but not ridiculously so. He’s stoic, poised, speaks up when necessary – and remains a strong leader in spite of toning back the ostentatious aspects of his real life, and what would later become a caricatured Schwarzenegger screen persona in latter fare like Last Action Hero, True Lies, Eraser, Jingle All the Way, and Batman & Robin.

The Arnold recipe for success became delightfully predictable around 1990, but was ingenious in many ways. Just take a healthy dose of toned torsos, a heavy measure of heightened sci-fi world-building, a tinge of tension-breaking one-liners, a dash of disarming humour, add a propensity to always win, and out slid action classics like The Running Man and Total Recall.

“I knew I was a winner back in the late sixties. I knew I was destined for great things. People will say that kind of thinking is totally immodest. I agree. Modesty is not a word that applies to me in any way – I hope it never will.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Ivan Reitman’s Twins and Kindergarten Cop, were branded as the movies that, “Proved Arnold could act.” This was quite harsh and dismissive, and I feel it underrates his work the year prior in Predator, where he displayed gravitas in a challenging starring role, rarely resting on wisecracks or catchphrases (outside of “Knock knock,” and “Stick around,” anyway) to, along with McTiernan, covertly spoof the action fare of the ’80s during the intentionally overblown raid on the guerilla camp. Reitman’s work with Arnold showed he could do comedy, and would make fun of himself, and lampoon his carefully-crafted on-screen persona. Yes, they were softer stories with him playing somewhat against type, but for me at least, even prior to Twins in ’88, ever since Commando, really, we were always laughing with Arnold. He was somewhat of an unlikely all-rounder, appealing to the wrestling-obsessed kids and adolescents, and the manly men. He also emerged as somewhat of a fetishistic love interest, attractive to select female audiences, too.

I found myself in the unusual situation of agreeing with sweater-vested whingebag, Gene Siskel (twice, no less) when he stated, “You wouldn’t call Sylvester Stallone “Sylvester.” You wouldn’t call John Wayne “John,” but we call Arnold Schwarzenegger “Arnold.” Also, credit where it’s due, my other Rewind Movie Podcast nemesis (not really), Roger Ebert, wisely pointed out that Arnie, in his human roles, plays baffled and bewildered particularly well. Perhaps it’s his default setting. An, “Is this really happening?” factor seemed to colour his choices. He can play, “What is this unseen creature out there in the jungle?” to a T. In The Terminator, he’s literally a robot, which works like a charm. Then, he played against type. Just as (or perhaps after) things were getting predictable, Reitman’s Twins, Kindergarten Cop, and weakest of the bunch, Junior, showed another side of Arnold, and ushered in more self-deprecating humour.

Granted, the suitably wooden-monikered, “Austrian Oak,” was never the most talented thespian working in Hollywood, however, there’s an argument he was one of the most self-aware. He recognised his limitations, handpicked solid scripts, and showed a confident, yet measured understanding of his weaknesses – but most importantly, he clung to and nurtured his potential, and manifested success. He propped himself up with the preeminent professionals of the era in front of and behind the camera, and held the reins (comparatively) tightly, maintaining a not exactly flawless, but respectable amount of quality control over his career trajectory. His heyday, for me, is neatly book-ended by James Cameron’s first two Terminator films between 1984 and 1991.

Schwarzenegger’s cynical (which I hate), nevertheless highly effective marketing approach, can often rub me the wrong way. Personally, I have an aversion to self-branding. It always feels contrived, and a little dishonest somehow, as do the sellout Japanese rake-in commercials “Schwarzy” happily hopped into – this seems as far from artistic integrity as actors can possibly get. I’ve always been comfortable thinking more like an artist and less like a businessman, but, as I’m sure Arnold would inform me, that won’t score me the big bucks anytime soon.

He’s a deeply ambitious man, clearly conscious of his own political aspirations – so much so, that he attempted (in vain) to crowbar his “trust me” catchphrase into several of his motion pictures. Admittedly, it didn’t click like “I’ll be back.” Regardless, he lived, and continues to live, the “American Dream,” having initially identified somewhat of a violent desire lurking beneath it, and fulfilled the public desire to splash it all over the big screen with hard R sci-fi horrors, then wisely pivoted to quench the audiences’ thirst for late-eighties family-friendly entertainment. He always seemed to be tuned in.

Albeit flawed, Arnold is a bona fide cult celeb, with broad appeal across the board. A smart, shrewd guy, who always understood, and evidently continues to understand America, how to play the game, and always win.

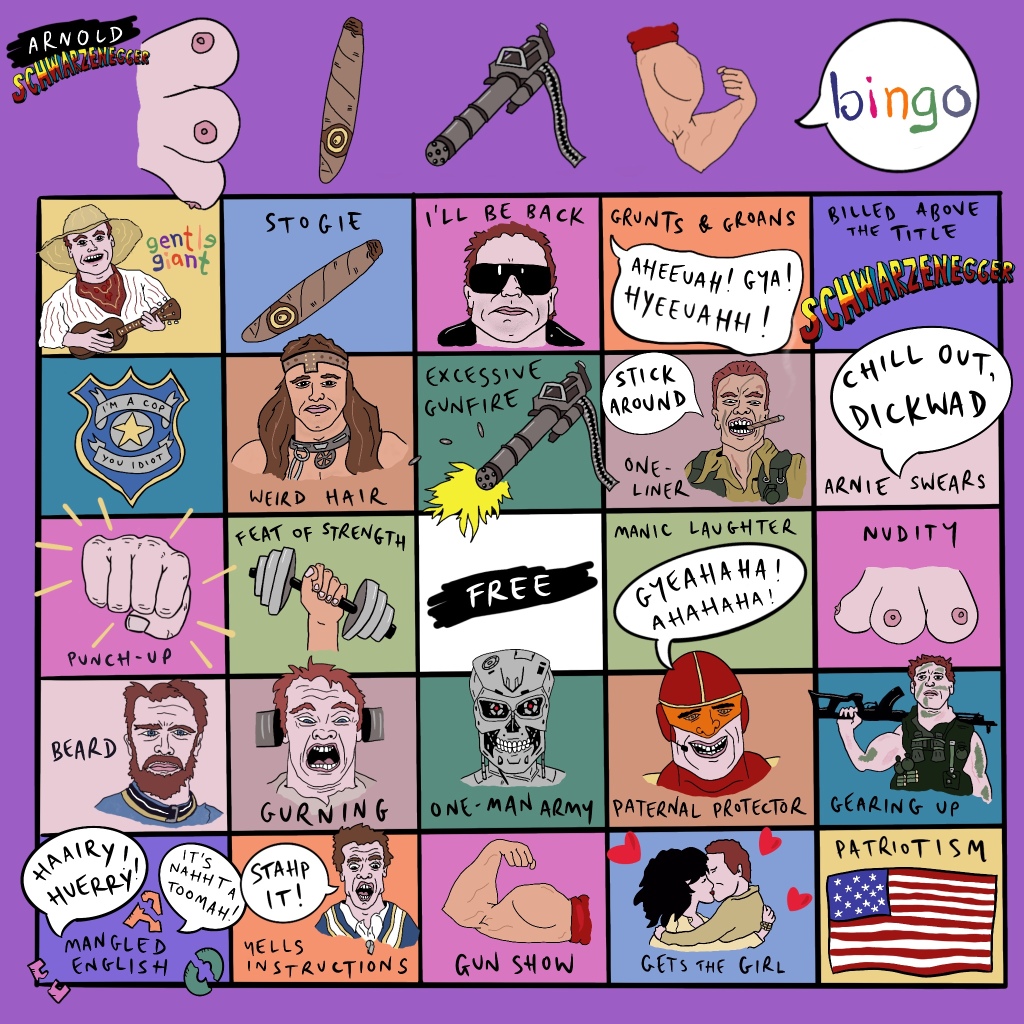

Arnold Schwarzenegger Bingo

Feel free to sit back, break out your beverage of choice (I’m not talkin’ protein shakes here), and perhaps a tequila-dipped stogie, and play the most dangerous game of Arnold Schwarzenegger Bingo (now also available as a handy Trope-Tote™).

You must be logged in to post a comment.